Today in 1972 saw the all-day London Rock and Roll Show at the city’s Wembley Stadium. It was a one-day festival which served to draw the cultural line between those who wanted to appropriate/update ’50s pop culture and those who held to it with all the force of, to use a word used by Jon Savage in discussing the day’s events, “fundamentalism”.

The bill was a remarkable mix of the old and the new, as you can see in the scan below:

The die-hard rock and rollers in the audience, containing within their ranks a large component of flat-out Teds, made up the majority of the slightly disappointing crowd of 35 000. And they made it absolutely plain that they wanted nothing to do with modern-day adaptations of Fifties rock and roll. As a consequence, the likes of The MC5, Roy Wood’s Wizard and Gary Glitter fell well short in the audience’s affections. No amount of obvious reverence for the source material and energy in performance could bridge the gap between what the partisans in the audience wanted and what more contemporary acts could provide.

Even famed rock and roll pioneers like Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis failed to receive the reception we might expect. The former seems to been lost in excesses of self-regard during his act and completely lost the audience, being, according to the NME, booed off stage, while the later was conspicuously late on stage and, in the words of Time Out’s John Collis, “almost blew it”. They simply hadn’t played the game according to the rules. By all accounts, the most successful acts were Chuck Berry and Bill Haley, the latter of whom, according to Collis, “stole the show”. Haley’s career doesn’t sit well with post-1956 notions of authenticity, but they rarely take into account the loyalty felt by Teds to the first rock and roll star to be widely acclaimed in Britain. They simply loved him. One commentator suggested they adored Haley even more than Elvis Presley.

It was a very odd cult indeed, resisting not just the present and the future, but the past as it had been lived as well.

Just a few years before, the small number of Teds in London had been the subject of a 1970 Sunday Times Magazine cover story. There were, the piece reported, only just enough of them to keep the single Black Raven pub in business. Between then and the Wembley festival, their numbers had, contrary to all expectations, swelled. The same cultural wave that saw rockers like Creedence Clearwater Revival, revivalists like Sha Na Na and ironic adopters like Roxy Music rise in their own way to prominence also carried with it an ever increasing number of backwards-staring rock and rollers.

Their reverence for a particular idea of a honoured and honourable past seems to explain a great deal about how they responded at Wembley. Their’s wasn’t an identity marked knowingly by playfulness. They were serious. Not just keepers of the flame, but its guardians too. At the London Rock And Roll Show, reports say that relations between the faithful and, for want of a more appropriate term, the heathen were generally good. But in the period as a whole, Teds were reclaiming much of the reputation for violence that they’d relished in the Fifties and early Sixties. It’s no surprise to recall that they declared war on Punks in the second half of the decade. In the latter’s appropriation of Ted fashion lay, to the territorially humourless rock and rollers, a deliberate and disdainful heresy.

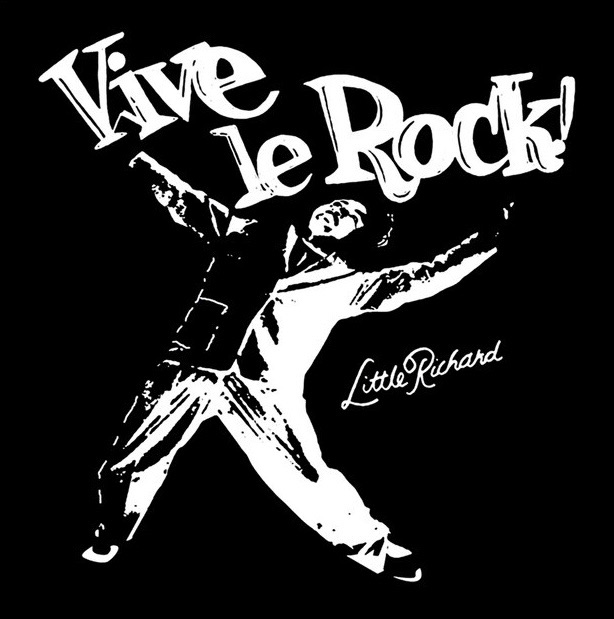

Famously, Malcolm McClaren took a bath with one particular design of t-shirts he’d printed up for the day. Truth was, he had completely misjudged the marketplace he’d hired a stall to sell to. At the time, he and Vivienne Westwood were, of course, making their living selling 50s fashions and memorabilia to, mostly, Teds and their fellow travellers from Let It Rock on the Kings Road. But McClaren’s efforts to flog a special t-shirt at the Wembley event went awry because he was attempting to speak, unknowingly, to two different audiences. He hadn’t realised it, but he was reaching out to both the devoted and the casual with a black top featuring the words Viva La Rock and a shot of Little Richard marked out in white negative space. His considerable order largely failed to shift. Whatever else he and assistants sold on the day, and the film of Wembley features a scene of them doing brisk business, the conspicuously new failed to find a significant audience. It was simply lacking the illusion of authenticity to hardcore rock and rollers. What in the sacred imaginary Fifties had ever looked like that? (McClaren did at least get the NME’s coin, as the paper had its four critics assigned to the show kitted out in his shop.)

Rock and roll had long been the vehicle for McClaren’s dreams of sartorial and social rebellion. That wouldn’t remain so once Wembley was over and done with. There would have be something else, something new, something fresh and exciting. Whatever that might be.

Wilko Johnson played that day with his Dr Feelgood colleagues in the band backing low-burning early 60s singer Heinz. It was an experience, Johnson would repeatedly say, which did for any desire, or even willingness, on his part to play to British rock and roll audiences. To Johnson, as he told Zoe Howe in 2012, the “Teddy Boys were a bad lot … they want(ed) Twenty Flight Rock and nothing else”. It was an opinion he’d held fiercely ever since Wembley. In Mick Gold’s Rock On The Road from 1976, he was quoted as saying the rock and rollers were “based on a fiction … (They) wanted to hear a kind of music that never really existed. They thought if you didn’t wear a drape suit, it wasn’t classical rock ’n’ roll, but no singers ever dressed like that. Chuck Berry never (did)”.

Or as Mick Jagger put it in the film of the event, “It’s a fossilised scene.”

As such, the London Rock And Roll Show was a prime example of an anti-fantastical event. Yes, it was certainly grounded in a fantasy of sorts, but one which was ossified, excluding and policed with the fervour of the heavy-browed acolyte. In a year of the most fabulous reinventions of fantastical traditions, rock and rollers opted to step determinedly backwards from tomorrow. Change was unwelcome, challenge anathema, ambiguity threatening. Their future was a static, bleak, one-dimensional vision of a yesterday that had never existed. Fine for those who felt they belonged there, and surely a tremendous amount of fun for those who had fun in that way. (The jukebox at the Black Raven certainly sounds fantastic.) But it wasn’t a world for everyone else. Like all fundamentalist regimes, it was only for the committed.

And that just wasn’t a place where the fantastical could thrive.

The Almanac Of The Fantastical will return tomorrow …