Heaven only knows how many fans were buying UK comics zines in the early 1970s. A few hundred? Somewhere in the (very) low four figures? Whatever the figure was, it was tiny, and the same names would often appear across a number of different fanzines as writers and correspondents. In and around London especially, there seemed to be a small hardcore of enthusiasts that had all known each other for a considerable amount of time. Letter columns could feel, to the outsider, as if they were continuations of debates begun earlier, and often elsewhere too, in other fanzines or on the floors of little comic marts and in the bars nearby. Mostly the same taken-for-granted canon underpinned conversations, although it shouldn’t be imagined that disagreements and outright feuds were uncommon.

Adzines offered the chance to buy through the post what couldn’t be found in the shops. Newszines focused mostly, but not exclusively, on information from the US, whose characters and publishers British ‘aficionados’ often seemed to be most interested in, and which was typically funnelled over to Britain from the States’ own comics fans. Given how limited resources were, the British comicszines were frequently both informative and enjoyable.

In a culture which despised all but a few comics, the fanzines helped readers feel as if their interests weren’t either as rare or as inextricably abhorrent as it could seem. For me, and many others, they were essential.

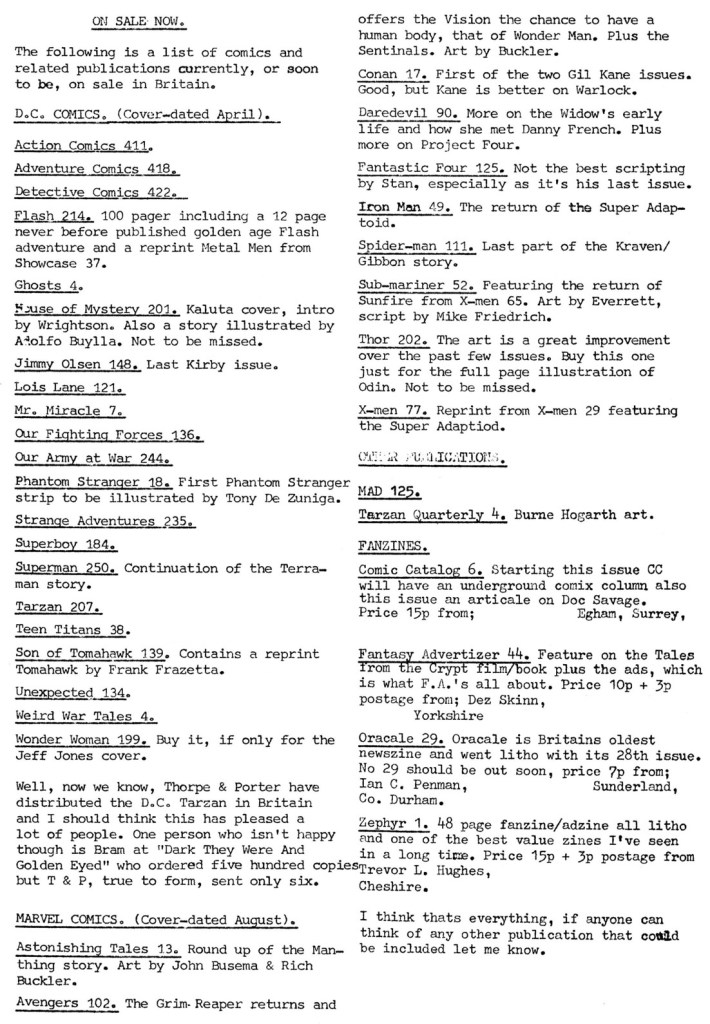

Editor Rob Barrow’s Fantasy Domain was always worth picking up, and even now, decades and decades later, it’s a source of fascinating information about the comics marketplace and fan networks of the period. The page above is a splendid example. Knowing what was, and most importantly wasn’t, going to be imported from America was a vital business. It was tough enough to actually find the comics that had been officially distributed. But the hours spent searching for, and dreaming about, comics that would never be brought over were a thorough waste of time and dreamspace.

Here, the likes of Barrow’s reporting from the distributors was a godsend. It certainly reveals how confusing collecting was. The DC Comics which were to appear in British newsagents came with an ‘April’ cover stamp. But the Marvels, although frustratingly fewer in number, were more recent and marked ‘August’. In short, one company’s imports had first appeared months before the other. These disparities, which could change from month to month, made it harder for the everyday reader to work out what was, relatively speaking, new and what wasn’t. It also makes it very hard to work out today what was available at any one time in this period in the UK. Just because there’s a record of one company’s books being available over here in a particular month doesn’t mean we can assume anything about those of its competitors. Later on, things would become more predictable. But then, later on brought long months when Marvel’s titles in particular didn’t appear at all.

If nothing else, this shows how different the everyday experience of comics fans on either side of the Atlantic could be. Over in the shining city on the hill, they were permanently living in our future. What had still to turn up for us, and perhaps never would, could be old hat to them.

It’s worth taking a moment to comb through Barrow’s lists to note what comics weren’t scheduled to come over. To my surprise, distributors Thorpe & Porter intended to bring over every DC Comics’ title that was new and fantastical except for, above, the gothic romance of The Dark Mansion Of Forbidden Love. That wouldn’t, however, have been an absence bemoaned by fandom’s majority devotees of superhero comics.

But the same couldn’t be said for the Marvels which weren’t being distributed. I’ve left their covers below for you to peruse. They include titles starring key characters whose adventures were central to the ‘Marvel Revolution’ of the 1960s, such as Captain America, Ant-Man and The Hulk, alongside newly-launched features designed to broaden the company’s readership, with the horror stylings of Ghost Rider, the Blaxploitation of Hero For Hire, and the more thoughtful sci-fi of Warlock. These were indisputably vital titles and they weren’t coming over. Comics which could seem plentiful in number and commonplace in America were immediately rendered collector’s items over here. Being a comics fan in the period could be immensely confusing, frustrating, disappointing and expensive.

(You can read scans of many of the period’s comics fanzines at David Hathaway-Price’s essential Fanscene site, and essential it really. is. I’m fortunate to have, for example, the run of Fantasy Domains, but there’s so much at Fanscene that I don’t have. It’s a key resource and flags should be waved in celebration of it.)

The Almanac Of The Fantastical will return tomorrow…