In the years before Far Too Much became A Very Bad Thing for all but our lords and masters, America was A Very Good Thing Indeed. Older generations might have balked at our enthusiasm, but we knew, or rather we felt, that they were just plain wrong. The traditional, disapproving view of Americans as vulgar, no-nothing, brash chancers had been fatally undermined by the ever-swelling number of what our betters saw as vulgar, no-nothing, brash British chancers. Americans weren’t cautionary tales, they were role models, and what we wanted was citizenship of a mythical America characterised by glorious excess without limit or consequence.

Looking back, our childhood ambitions were hardly unbridled. We just wanted Saturday morning cartoons that started at daybreak and ended after midday. We wanted 24/7 FM rock radio and 7/11 connivence shopping . We wanted bottomless portions of chips, no, French Fries, and cold chocolate shakes so dense with chemical additives that swallowing, let alone digesting, was a serious challenge. (But what was life without challenges?) Did it really matter what cartoons they were, or what milk shakes? As long as they were alright, they were fine, and if a single substantial measure was enjoyable enough, then why not a dozen more? The very concept that indulgence could in any way be problematical was so vaguely held that it couldn’t even be considered theoretical in anything but the loosest sense.

And me, I wanted endless fantastical fiction. In America, there were, for example, a serious number of cheap monthly anthology magazines that could bulk out the dead looming hours of British life with spaceships and wizards and vampires. They could sometimes be seen in the UK, but as over here was, by comparison, as TV shows testified, far poorer and far more deprived than over there, it was only sometimes.

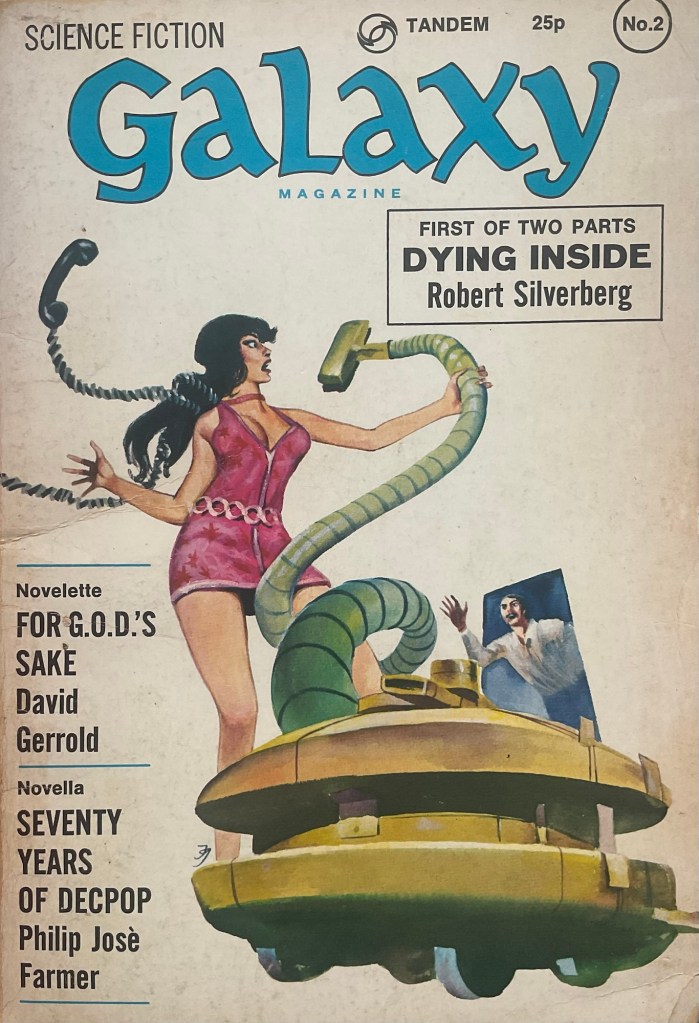

To read July/August 1972’s UK edition of Galaxy is to come face to face with a vision of what consumption for consumption’s sake can be like in reality. Far from a seductive package with a glossy futuristic cover, it’s a hefty, intimidating digest with cheap newsprint and 180 pages of largely unbroken text. Somehow it now feels far more like a chore than a pleasure. Some of its content is undeniably very good indeed. The extract from Robert Silverberg’s Dying Inside certainly reminds me of how fine the novel, and even in its heavily cut first published version, is. But it’s incomplete, and some of what it shares space with is, inevitably, less appealing. Anthologies tend to appeal when they can deliver something that other price-comparable options can’t. Ironically, in a time of consumer excess and disposable income, the compact heft of the likes of Galaxy can’t compete. As soon as I could afford to fill up the hours with fiction magazines, which I so longed to do, I found I could afford other, more attractive things. The likes of 25p for a copy of Galaxy was once a darn good deal. In the decades when the (now swiftly ebbing) consumer boom was only slowly gathering pace, and when technological alternatives were as yet unavailable, such magazines really were godsends. But in 1972, the same sum that could purchase Galaxy could buy a substantial and excellent paperback novel, complete in itself, with no ads or editorial digressions. And with an shiny, airbrushed cover too.

To hold a copy of a 1972 Galaxy today is to be able to feel – quite literally feel – why the vast majority of fantastical magazines faded away. They were wonderful ideas in theory. They were perfectly adapted to harder times and (sadly) shallower pockets. They were hugely valuable sources of information and even community. They offered newer writers experience and exposure, they lent established authors vital sources of income and space to, within limits, try something different. They were, in truth, a Really Good Thing. I mourn their passing and yet I wouldn’t care if I never saw another one for sale again.

It seems I still want precisely what I want, in never-ending quantities with rarely-varying flavours. I still want to eat/watch/drink/drink/play forever. I want mountains of unread books and unwatched movies. But the nirvana of endless consumption is no longer enough. It’s a disturbing realisation. Now I don’t want something I’ll probably like. I want what I love in undiluted and uninterrupted forms. I’ll take chances, sure. But I’ll be pretty sure, after recommendations and samples, that I really want what I’m taking a punt on. In essence, I used to prefer chocolate milk shakes. And now, I’m an exclusively chocolate shake man. It’s what I like. Why would I reach for anything else?

Now I can afford anthologies, I find I really don’t, as a rule, want them. Down I’ve gone, into a solitary existence marked not just by excess, but an excess of exactly what I think I want. This is, surely, Not A Very Good Thing at all.

The Almanac Of The Fantastical will return tomorrow.b