Edmund Cooper wrote an awful lot of books. Many under his own name and many not. He penned novels and all manner of shorter stories and whodunnits and non-fiction and romances and criticism and technical pieces and stories for children and poetry. He wrote and he wrote and he wrote. (When I was stumbling through the first half of the Seventies as a boy, paperbacks of his fantastical novels seemed to be everywhere.) For 13 years, Cooper was also the Sunday Times’ science fiction critic, which, given that his reputation as a novelist of the form was in decline for much of the period, from 1967 to 1980, shows that, for whatever reasons, he was capable of discounting his own press while passing judgement on the achievements of others.

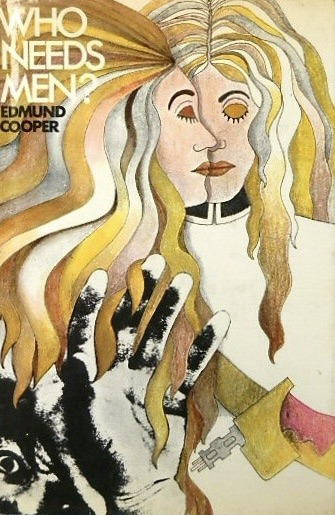

Yet Cooper had been relatively well-regarded at the very beginning of his career, as Robert Nye noted in his Guardian review of Cooper’s Who Needs Men? on this very date in 1972:

“I see an earlier reviewer compared him with Zamyatin and Orwell. This particular fiction is nearer the level of whatever American comic book it was that used to feature a female equivalent of Superman, who went about zokking and powwing folk and that at least had the merit of crude drawings probably now collected by male masochists.”

Nye’s almost-absolute scorn for American comic books suggests that his distaste and disapproval of Who Needs Men? might not be particularly valid. Snobbery and self-regard were clearly at work in his criticism. And yet, time spent with the novel reveals that the critic was a better analyser of sci-fi than he was of comics. When Nye described the book as “a sixth formish … satire on Women’s Lib … which spins out a basic whimsicality of no outstanding originality (marked by) the spotless tedium of the inane”, he was on baked-solid ground. (At the age of 10 or so, I was myself in complete agreement with Nye’s judgement, even if I couldn’t have begun to expressing myself with such insight, precision and contempt.)

Pat Feinberg’s pithy summary of Who Needs Men? in 21/7/72’s The Liverpool Daily Post spells out how slight the novel’s plot and theme are:

“…a world where women have taken control and are trying to exterminate men. What they don’t realise is that without the opposite sex they are little more than dummies themselves”.

When Who Needs Men? was issued in paperback, its back cover contained the following pull quote:

“Racy, with some nice touches typical of Mr Cooper”. Evening Standard

By racy, I take it the blurb is an attempt to sign up the likes of rape and orgies that exist inside the book’s cover. But more accurate, I’d contend, is the one word summary offered by Henry Tilney in Sunday 23rd December 1973’s Guardian, when he defined Who Needs Men? as being characterised by “windiness”.

The page from Who Needs Men? above shows Cooper’s satire of feminism at its most inventive and effective. This is not, evidently, a compliment. Cooper was certainly no obvious friend of the feminist movement. As quoted at the august SFE, which has been darn useful in the writing of this piece, he once declared:

“Let them compete against men, they’ll see that they can’t make it.”

And Who Needs Men? plays out that very belief, with the reference to the “semi-sacred shrine of Germaine’s Needle, formally Nelson’s Column” being as close as Cooper comes to wit. It was, of course, a period in which Germaine Greer’s cultural reach as a feminist writer and activist was, justly, considerable and unprecedented. Whatever the response to her epochal 1970 feminist tome The Female Eunuch, and it was often debated keenly and fiercely within the movement as well as beyond, it was a polemic that demanded attention, study and consideration. And it sold too. Lives were changed. Greer’s thesis that the structure of modern society crushes women’s sexuality and destroys them as vital individuals, leaving them as the equivalent to male eunuchs, helped to further detonate debate throughout the culture.

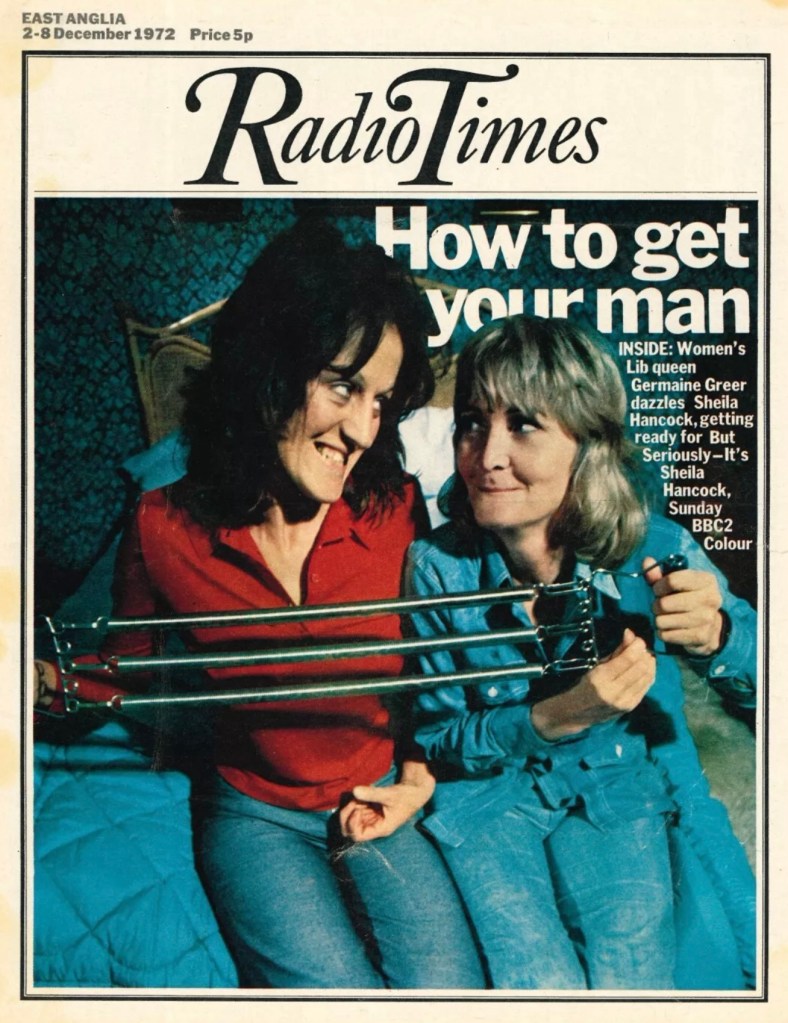

Germaine Greer was already a familiar figure to many when The Female Eunuch first appeared, and her fame in the period can be partially gauged by her appearance on the cover of December 2nd 1972’s Radio Times below. When Cooper portrayed her as an absurd icon of an uber-separatist future state, he was engaging less in a broad historical debate and more in a specifically contemporary battle of ideas. She, or the very least the use that her thought might be put to, was both silly and dangerous.

Ironically, it’s Cooper’s cack-handed satire that has most helped to lend the novel a life beyond its first few print-runs. For that very mix of popular culture and political jousting has meant that Who Needs Men? is of interest to 21st century cultural historians. The book as a work of fiction is pretty much forgotten in sci-fi itself, although nothing goes without rediscovery and there is a gathering of new support for it in this age of the seemingly infinite net. (One genuinely smart-minded and positive reviews of the book is to be found here at Trash Fiction, which undeniably deserves your attention in its own right, along with serving as a counterweight to my own shameful bias.) And when discussed as a marker of its time, praise can arrive that hasn’t always been forefront in the novel’s reception. In Alwyn W. Turner’s magnificent 2008 history Crisis? What Crisis? Britain In The 1970s, for example, he writes that the novel is a “witty” burlesque …that reaffirm(s) humanity in the face of doctrinaire attitudes”.

Here at The Almanac Of The Fantastical, the opinion of Who Needs Men? is a particularly low one. But other takes, and takes of considerable value, are very much available.

The Almanac Of The Fantastical will return tomorrow.