The Perishers, like most of the rest of us, lived highly structured and essentially predictable lives. Anyone who’d read a year of their adventures could comfortably predict most of the set-pieces of the following twelve months. Readers knew that each October would, for example, find the inexplicably independent Wellington scheming to swell up support for his birthday celebrations, such as they were. On and on the same situations would roll around. Summer would see the gang on holiday by the sea and autumn would feature their reluctant return to school, and so on. It was all part and parcel of the strip’s central theme, namely, the never-ceasing quest to rise above other people’s expectations. There were nearly always, for good or ill, things that they were expected to do. At the heart of The Perishers lay a very gentle, British kind of anarchism rooted in the simple and straightforward desire to be left alone. In Collins and Dodds’ tales, we’re constantly presented with constraining situations shaped by habit, stupidity and unenlightened self-interest that intrude into the cast’s everyday lives. At every landmark of the year, life-thieving meddlers pursue their absurd goals. Sometimes these meddlers – and here we’re most likely to be looking at the intimidating Massie – are to be found in the strip’s main characters,

The brilliance of The Perishers at its height lay in the way in which the familiar conflicts between expectations and freedom were played out in slightly different ways. Predictable and familiar situations arrived, year and year out, like much-loved old friends. Massie attempting to impose her sociopathic expectations of what she called ‘love’ upon Marlon, the hopes and disappointments of Christmas and its traditions: readers would have been disappointed if these and many others didn’t reoccur on cue. But there was always something new in play too, even if only a minor twist in the formula.

It’s easy to see this at work in the strips concerning 1972’s holiday by the sea and Boot’s return to ‘the old rock pool’. Years before, the crustaceans in the beach water had seen Boot staring down at them and their self-appointed leaders had, in the absence of science or even sense, decided that ‘the eyeballs in the sky’ were of a central religious importance. From there, any number of orthodoxies and schisms had developed. Rules were invented, power was accumulated and challenged, ideologies perpetuated and undermined. In short, meddlers were about in the old rock pool too. Religion, the strip appeared to say, was unavoidably like that.

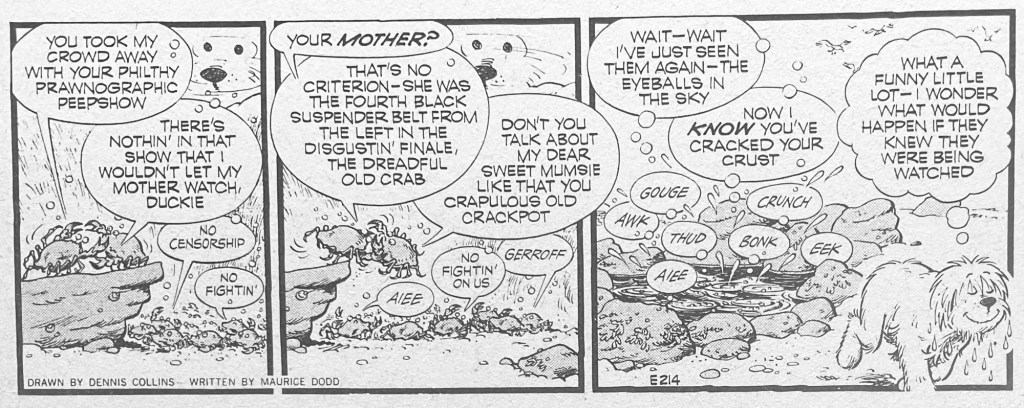

But 1972’s twist is also a poke in the direction of the then-current and fearsome debates about ‘The Permissive Society’. In the world of the crabs, the fascination of the young for all matters sexual was, to the elders, destroying the established social order. Why, even the annual return of Boot’s holy eyeballs was being ignored.

Of course, these are strips that take aim specifically at reactionaries such as Mary Whitehouse, the self-appointed guardian of public decency, and her censorious National Viewers And Listeners Association. It’s hard to imagine that Collins and Dodd were anything other than appalled, when they weren’t bemused by the ultra-traditionalist’s endless, shrill campaigns to ban this and punish them. It’s noticeable that the brawl in the rock pool is entirely the fault of the Crab’s ruling religious caste, who explicitly bemoan the loss of authority that sexual freedom triggers. If the lovers of Prawnography are portrayed as silly and somewhat obsessed, then what’s the real harm in that? It’s only when they’re forcibly poked by the Prawnography Probe that trouble occurs.

Neither knowing or caring what the fractious crabs are up to, Boot wanders away at the sequence’s end while wondering what the pool-dwellers would do if they became aware of being watched. (It’s even now sobering to know that the kind of human models for the crabs can be very much aware that they’re been seen and only made worse by the awareness.) Now, it’s not that Boot is the voice of scientific reasoning here. (He does, after all, consider himself to be a reincarnation of the cursed soldier Lord Boot from the eighteenth century.) But on the whole, Boot is always happy to leave well, or even its opposite, alone. In that, he may not be a heroic figure, but he is a role model. Heroes, after all, have a terrible habit of, well, meddling…

The Almanac Of The Fantastical will return tomorrow …