Nostalgia insists that the American comics released in June 1972 were pretty much all fabulous. But the truth is, and I can’t say I’m happy to admit it, that they mostly weren’t. The turn-of-1970 burst of energy and creativity that had charged up so many of DC’s comics was already ebbing, while Marvel’s titles, sadly, often pulled off the trick of feeling both formulaic and directionless. Still, there were a few classics released during the month alongside plenty of perfectly pleasant books, so here’s my nominations for June 1972’s five best comics.

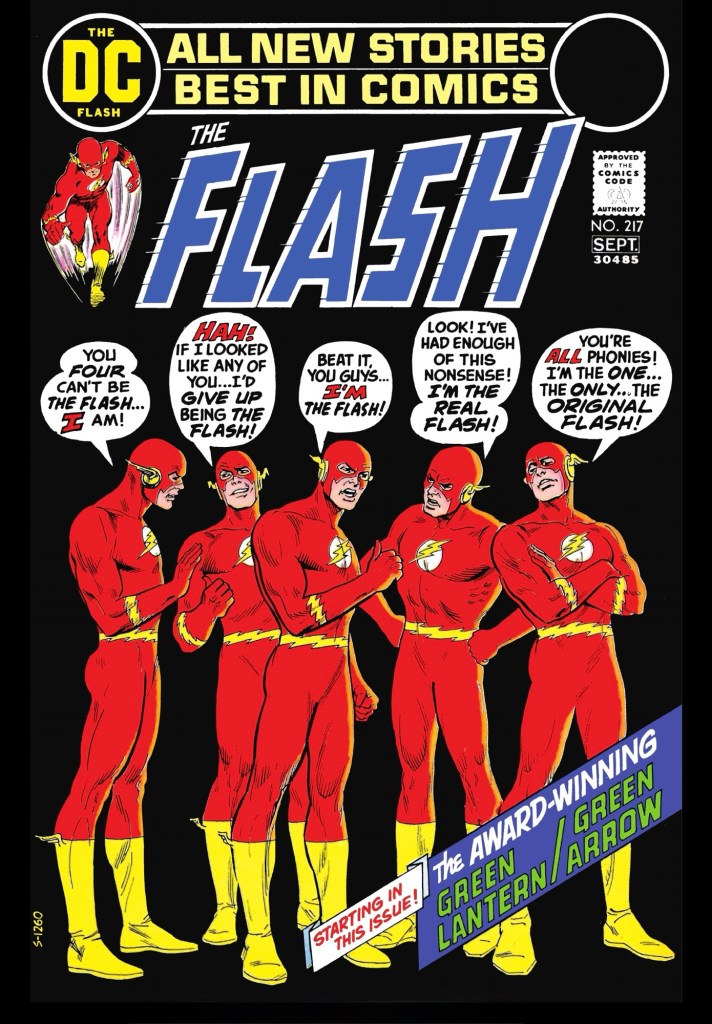

I doubt many would add the title story in Flash #217 to a list of the character’s finest tales. But as minor it is, it’s also a highly professional confection – by writer Len Wein and artists Irv Norvik and Frank McGlaughin – that delivers exactly what the cover promises, namely, Barry Allen divided into five squabbling versions of his costumed identity. Sadly, there’s little on the page that adds anything of substance to the events on Nick Cardy’s excellent cover. But as an meat-and-potato, month-in-and-month-out example of DC’s typically competent approach, it’s worth a moment of attention.

But best yet, the back of Flash #217 featured the return of Green Lantern/Green Arrow, whose own title had been cancelled just a few months before. (As a perfect example of the distance between the convictions of the cognoscenti and popular appeal, GL/GA had only recently made off with the prizes for Best Story, Best Penciller and Best Inker at 1971’s Academy of Comic Book Arts Awards.) The ‘relevant’ tales of O’Neil and Adams – the modern equivalent would most likely be ‘woke’ – had, when not bogged down in an excess of worthiness, felt well ahead of their time. Whatever its shortcomings, GL/GA felt cutting edge, contemporaneous and dynamic, and it was definitely not for the kids. Did that mean it was the fabled superhero title that would appeal to – whisper it – adults? Well, perhaps, and perhaps not. But even in a short burst at the back of another character’s book, GL/GA still shone out as fresh and forward looking. In fact, the difference between the storytelling of the GL/GA creative team and that on the Flash tale only made the former seem more impressive and the former more comfortingly traditional. Together, the presence of both strips made Flash #217 feel both substantial and special, the past and future working to each other’s advantage.

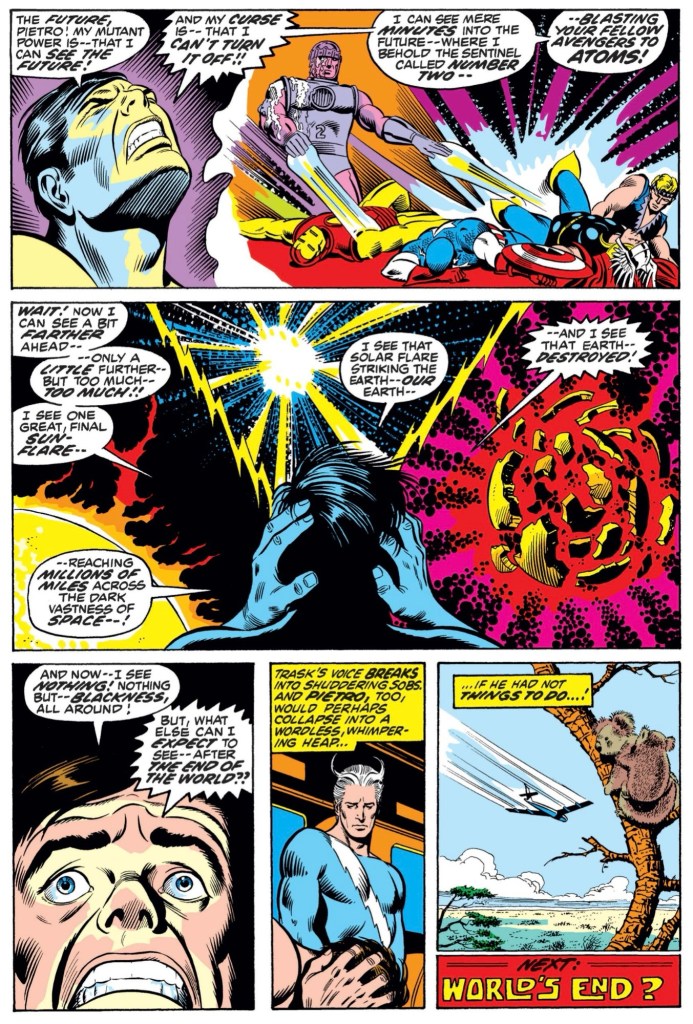

The second of a three parter featuring the Sentinels, from back when their appearances were rare and their menace accordingly greater, The Avengers #103 is a prime example of how good a plotter and scripter Roy Thomas was during the period. It’s impossible to think of a single artistic team that didn’t rise to, and amplify, the opportunities offered by Thomas’ outlines during his years-long stint on this title. Here, Buckler and Sinnott, my own favourite collaborative partners for Thomas on The Avengers, weave a wonderfully compelling variety of set-pieces which include Antipodeon punch-ups, intense one-to-one conversations and even events fleshing out 1960’s X-Men adventures.

Perhaps the best example of the strengths of the creative team can be seen on the comics’ final page. The end of the world is a commonplace in superhero comics, and that was as true in 1972 as it is today. But seeing the apocalypse through Lawrence Trask’s eyes adds a fresh and personal spin on matters. It’s hard to imagine any superhero fans reading these panels and feeling blasé about catching the trilogy’s conclusion.

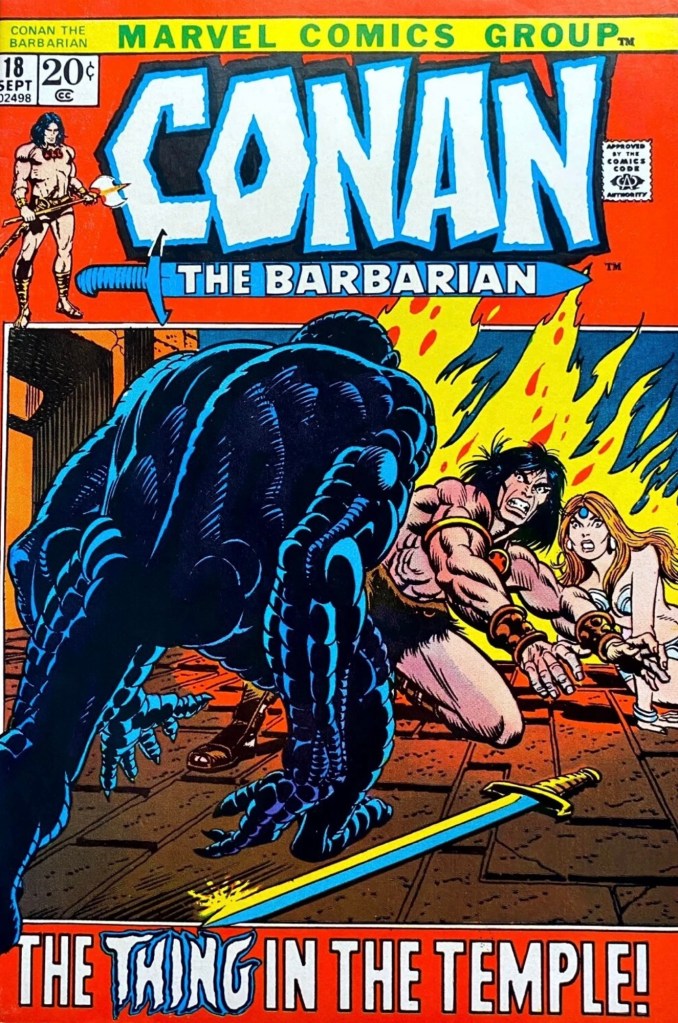

Thomas’ standing as one of the best of the non-artist storytellers in the period’s mainstream was only underscored by the excellent Conan The Barbarian #18. But in a way, his work here was somewhat overshadowed by that of his artistic collaborator Gil Kane, herein inked with impressive sympathy by Dan Adkins. For Kane was a newcomer to the pages of Marvel’s regular Conan title. Until this two-part tale, the book had been, from its very first issue, home to Barry Windsor Smith’s storytelling, and the rapid and innovative development of his art over the period had offered readers a kind of parallel narrative to the comic’s stories. For Smith had begun as an admittedly ambitious artist heralding noticeably from the School Of Jack Kirby, and then began to significantly polish his skills while incorporating unconventional non-comics influences from the likes of the Pre-Raphaelites and the French Symbolists. The consequence was a very different depiction of Conan and his world to that seen in the likes of, for example, Frank Frazetta’s paperback covers. Smith’s Conan didn’t lack for power, melancholia or rage. But he was often remarkably graceful and even – whisper it – strangely beautiful. As with the character, so with his world. It was a process of both evolution and revolution which became more wonderfully obvious, in this way or that, with each passing issue. And yet now, the reader was faced with the work of industry veteran Gil Kane, who, with inkers Ralph Reese and Dan Adkins, had taken the helm for a two-part adventure. There were no trace elements of Rossetti or Moreau in Kane’s art. His was a far more traditional Conan.

What remains remarkable is how completely and utterly Kane and his embellishers made Conan their own. There could never have been the slightest doubt that Kane would have delivered a pacy and thrilling tale. His had been a long and impressive career, and, in the likes of the pages of his own Blackmark, he’d had previous in the blood and thunder of sword and sorcery. But his success in making Conan all his own was still remarkable. It didn’t so much replace Smith’s depiction so much as stand as an equally valid interpretation. Yes, it was a more traditional approach, which offered none of the shock of the new that Smith’s art did. But such was the imagination, dynamism and invention present in Kane’s art that it stood, and still stands, as one of the definitive comic-book takes on Conan. The page above should help underscore the point.

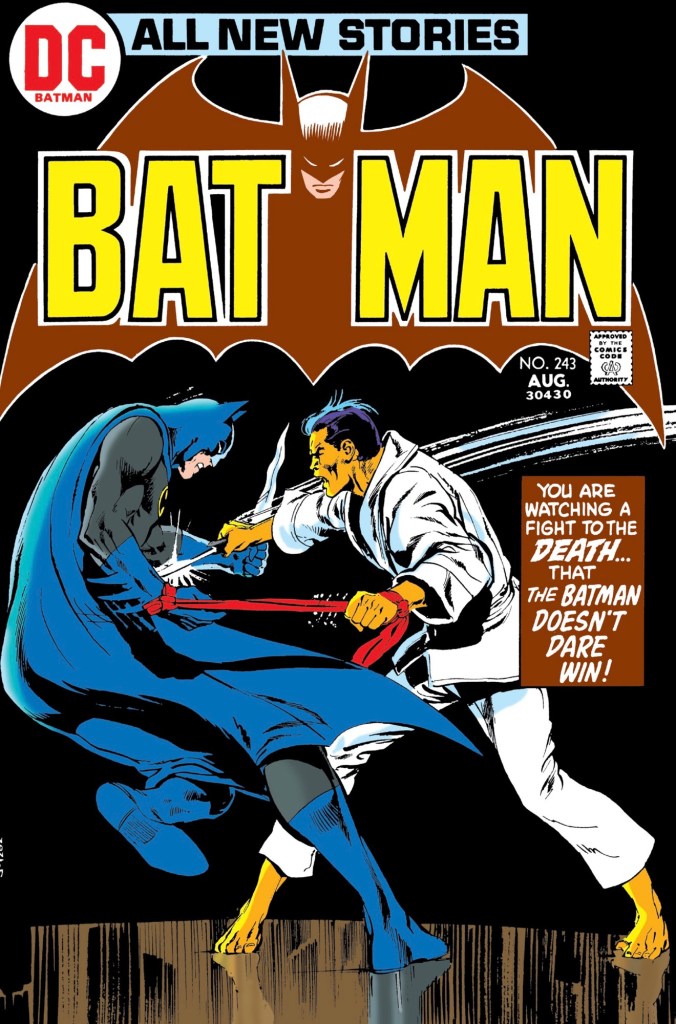

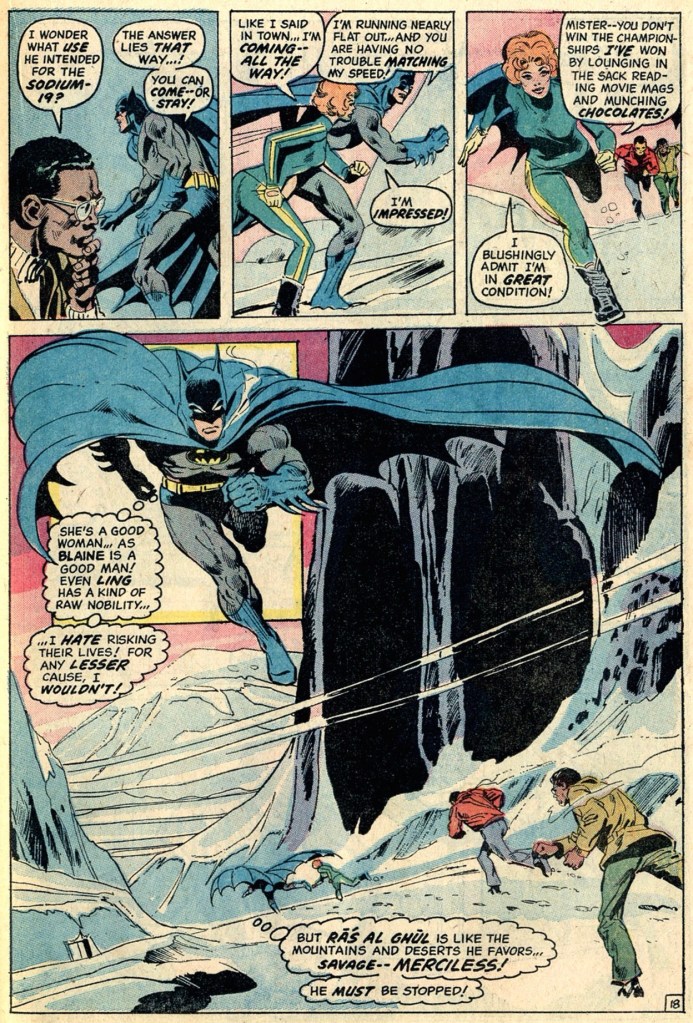

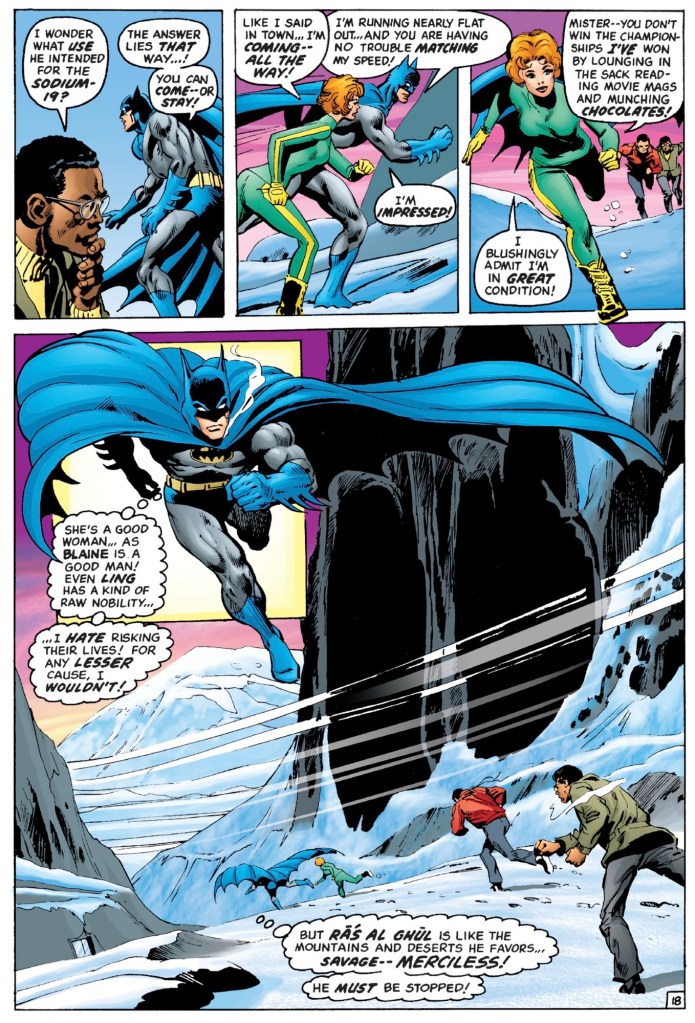

The same names turn up repeatedly in most discussions of 1972’s best US titles. The industry was on the cusp of the arrival of a substantial number of hugely promising new creators, but as yet Marvel and DC were still reliant on a relatively small pool of talent. At the forefront of its writing staff were writers Thomas and O’Neill, the latter of whom helmed, in addition to the aforementioned Green Lantern/Green Arrow, Batman #243. With him, again, was the great Neal Adams. For both men, and to their credit, the Batman tale seems to have demanded a very different approach to that of GL/GA. In this episode of Batman’s on-going war with Ra’s al Ghul, their story drew not on relevancy and action as a tool of character development, but rather on a series of very familiar action/adventure traditions. From martial art stereotypes to James Bond set-pieces, the tale felt as if it had been deliberately and enthusiastically bolted together from disparate sources. The result is an international thriller which moves at such a pace, and is told with such skill and enthusiasm, that its patent implausibilities are, on first read, easily sidestepped.

None of this is to diminish the story’s revelatory epilogue, in which we’re introduced to the resurrection machine that’s Ra’s al Ghul’s Lazarus Pit, a fabulous invention which offers its owner immunity from death, a vastly extended life-span and some terrible psychological consequences. It’s the first part of this tale that feels fresh, impressive, and even, yes, thoroughly sinister too, and it caps a frantic chapter with a quite brilliant conclusion. Rarely if ever has The Batman felt more vulnerable and outclassed.

(Above I’ve posted a page scanned from the original comic followed by the version of it now offered both digitally and in print reprints. A prime example of how not to reboot art, it’s garish and distracting and so different to the original that it ought not to be pushed as its official, and thereby seemingly definitive, version.)

We know that at this point in time, Jack Kirby had already swallowed the cruel cancellation of the New Gods and The Forever People and was already delivering completed issues of their replacement titles. Perhaps as the result of that, New Gods #10 feels under-powered by comparison with its predecessor. In truth, I’ll reluctantly concede, News Gods #10 feels as if Kirby had been asked to aim his work at a younger and less committed audience. Had he already moved on? Or was he responding to previous suggestions from on-high about tightening the focus of his previously-sprawling magnum opus ? For those of us who loved that high-concept sprawl, with its almost-overwhelming mass of new and fresh and beguiling concepts, the very idea of reworking Kirby’s approach was as absurd as it was unwelcome.

But even what seemed, rightly or not, like less-ambitious Kirby storytelling was still way ahead of most of its competitors. The epic scale of the Fourth World was still palpably present, the fight scenes were still dynamic and involving, and the touching friendship between Orion and Lightray still grounded the series’ mythos with a convincing emotional depth. As such, New Gods #10 sits very comfortably in my choices for the best five American comics from June 1972.