Continued from yesterday’s post:

1. I’ve seen Rocket Man take some terrible stick recently. The tune’s shamefully derivative, the lyrics are embarrassing pap. Let me once again declare my membership of Those That Don’t Know And Can’t Understand. I think it’s a gorgeous song, sad and beautiful and, cuss me if you wish, insightfully played out too. “Mars ain’t the kind of place to raise your kids”, and the lines that follow, obviously sound like dumb-brained hackwork to some critics. But to me, I think they’re sad and touching and, why; I may just have to listen to Rocket Man again right now.

2. I’ve not placed Starman after Rocket Man through any sense of mischievousness. Yes, Bowie appears to have thoroughly hated Elton John and Bernie Taupin’s song, and yes, it’s hard to imagine Rocket Man existing if Space Oddity hadn’t come before it. But it is fascinating to note how very different the three aforementioned songs are in terms of their meaning. In Space Oddity, the celestial scale of the cosmos appears to cause Major Tom to concede his own relative insignificance in the scheme of things. In Starman, the universe is, by contrast, a crucible of wonder and fun, intelligence and even salvation. But in Rocket Man, space is simply a place to travel through and labour within. There’s neither epic grandeur and the perspective it lends or a science-fiction wonderland with interstellar spacemen bringing hope and inspiration. Instead, existence out there is just another disenchanted realm for alienated wage slaves. In that, Mars is even worse than Earth. As a place to slog away the hours as a wage slave, it’s without either meaning, beauty or comfort. It doesn’t cause the illusion of individuality to dissolve or kick-start an exciting new perspective on life, the universe, and everything. It’s just the endless reach of Earthly capitalism, only even worse. No wonder Rocket Man sounds so darn sad, so absolutely broken.

3. There’s no lyrics to be found in Billy Preston’s marvellously exuberant Outa-Space, so the more literal minded might worry that the funk work-out’s meaning is, with any degree of precision, tough to discern. But that’s literal-mindedness for you, and I write as somebody whose ASD makes him a perpetually baffled slave to it. But such is the joyfulness of Outa-Space that it’s next to impossible to imagine Outer Space as anything other than an unimaginably fabulous destination. In truth, Preston could have titled the track The Black Death or The Fall Of Minoan Civilisation and the implication would have been that we’ve all misunderstood what a staggeringly fine party those historical moments constituted.

4. I wonder if anyone knows the precise meaning of Blue Oyster Cult’s Workshop Of The Telescopes. (There’s fun of a kind to be had reading speculative line-by-line interpretations on fan forums.) Part spell and part record of the spell’s reputed effectiveness, Workshop Of The Telescopes has the considerable virtue of sounding as if it’s grounded in some kind of authenticity. Are we talking alchemy here? Is this some kind of mystery cult induction? The guitars growl and twang without ever being allowed to break into any kind of tension-breaking riffing. The vocals mostly restrain themselves to growling. Brief moments of beauty are almost immediately brought to heel. More Hammer Horror than Carry On Magicianing, Workshop Of The Telescopes succeeds in sparking the question, do these guys really mean any of this?

5. For a great many years, it felt as Aphrodite’s Child existed only as a means by which the knowledge of progressive rock fans could be measured: which outfit contained both synth-master Vangelis and housewives’ choice balladeer Demis Roussos and released an epic concept album about the Book Of Revelations? It’s good to note, with the passage of time, that there are niches on the net in which Aphrodite’s Child are recognised for being a remarkably fine and staggeringly ambitious, if undeniably out-there, outfit. Those curious about the album might avoid starting with, say, the spoken word scene-setter that’s Loud Loud Louder or the guitar wigout that’s The Battle Of The Locusts/Do It and instead plump for the forceful, innovative and enjoyable rockers The System and The Four Horsemen.

It’s too easy to describe 666 with words like ‘mad’ or ‘berserk’. It’s too easy to throw it in the dumper with other hugely pretentious prog concept projects. It is mad, but then so is its source material. (*) At moments, I’ll happy concede, it does sound utterly berserk, but all involved prove more than capable of keeping their intimidating degree of ambition under purposeful control. As the decades pass, I can’t help but come round to the conclusion that it’s some kind of masterpiece.

- Other opinions are readily available.

6. The absence of the very qualities which allow Blue Oyster Cult to pull off Workshop Of The Telescopes are what makes Black Oak Arkansas’ Mutants Of The Monster such fun. There’s nothing of subtlety to be found in any aspect of Mutants Of The Monster. A sparse, slow blues punctuated by balls-out interludes of undiluted boogie, it finds the lacerated vocals of Jim Dandy Mangrum narrating a tale of human-created eco-horror and magic-inspired redemption. Only a return to nature, Mangrum insists, and the embrace of a shorter, bolder existence stands between the species and the perpetuation of monstrous homo sapiens.

It’s daft and rough hewn and a huge amount of fun.

7. The theme of so many of Ray Davies songs in the period is, in essence, a libertarian one. Why can’t people just leave him alone? Why can’t they leave everyone alone. If the powers-that-be aren’t threatening him and his with nuclear war, they’re reducing the vast majority of the species to brutal wage slavery. Too often, bemoans Ray, he’s been treated as a commodity far more than a human being, and forced to perform for a system that sees him as nothing more or less than a cash cow. Solutions offered, beyond simply leaving Ray alone, include the back-to-nature rejection of the 20th Century that we find in Ape-Man and its technology-embracing twin Supersonic Rocket Ship, in which a kind of freedom and innocence is to be found in outer space. The Utopian drive is very much the same in both. Touching in its sing-along simplicity and warm-hearted sentiments, Davies’ song promises his spaceship will be completely free of prejudice and exploitation. For the moment, the prospect sounds convincing and desirable.

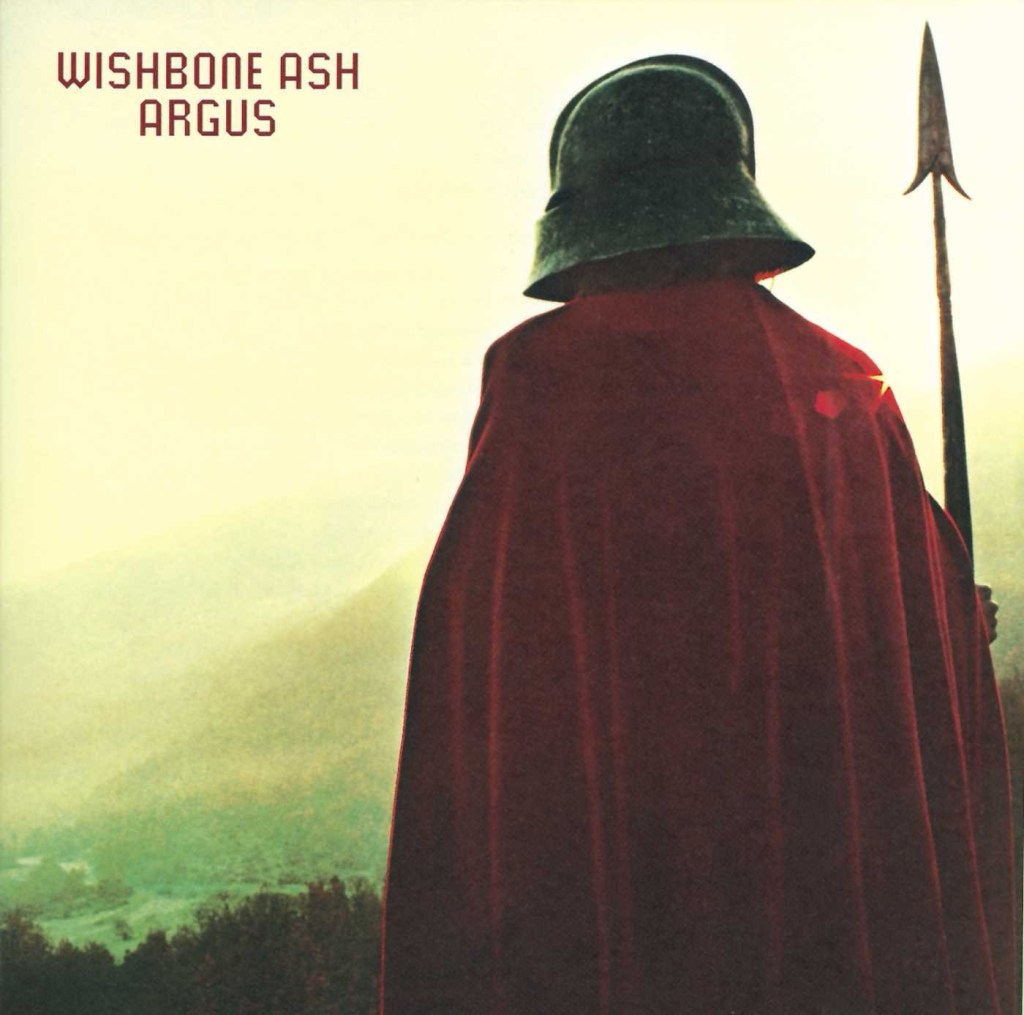

8. And finally, The King Will Come, by Wishbone Ash, which throws in a doubt or two where the then-traditions of so much of post-Tolkien fantasy was concerned. On the one hand, the track appears at first to buy into the archetypes of noble kings, evil regimes, wise prophets and peace-bringing warriors. Good over here, then, and evil over there, with little in between, we’re left to presume, save for the waverers, collaborators and cowards. Yet in contrast to, say, Mutants Of The Monsters, the warrior’s mission brings confusion rather than clarity. If there’s any answer to individual and social woes in the fantasy-tinged songs on Argus, they’re clearly not to be found in sword-swinging crusades. In the end, the ‘prophet’s words’ might – might – be prophecy. Or they might not. Destiny might not be showing its hand at all. We might be left all on our own to sort out the better from the less-good.

Wishbone Ash’s melodic sidebranch of progressive rock, with its innovatively harmonising twin guitars and folk colourings, sounds even now as if it was designed for sword and sorcery’s seductive nostalgia and violent flourishes. As an unfan who’s never paid close attention to the likes of Argus, it’s fascinating to see doubt nestling in its storytelling. But then, if a musical form feels suited to its subject matter, then it’s surely perfectly suited to a questioning of the same. Far too many others at the time swallowed the most basic readings of Tolkien whole. Argus doesn’t.