Given how the counter-culture had long embraced comic books, it should be little surprise to note that an early mention of 1972’s Comicon arrived in the pages of May 18th’s issue of the underground paper ‘IT’. There, amongst the pieces about Vietnam, rock festivals and Marcuse, and in the company of comic strips such as Gilbert Shelton’s Fabulous Freak Brothers, one ‘Bo’ reported – see below – that there would indeed a comics convention in the UK in 1972. (Reading through this from 53 years later, it’s hard not to think that everything had been left terrifyingly late.)

Several weeks later, in the Think Off column in July 1972’s Comic Catalog #6, the seemingly tireless and determined Nick Landau wrote that, at the time of writing, there had already been “over a hundred registrations” for the coming convention. Things were evidently moving fast for Landau, to his credit, given that he had never organised a Comicon before.

Comics fandom then being the small and geographically dispersed community that it was, national get-togethers assumed an understandable importance. Comicons were, for many, a rare chance to encounter professionals and fans alike. Yes, there were small clusters of devotees in urban centres such as London, Liverpool, and Glasgow, but they served as small cells in a country largely unmarked by meetings between fans. At a convention, names which had previously existed only on the pages of fanzines, which themselves had at best three-figure circulations, could be attached to the sight of living, breathing human beings. Best yet, a Comicon promised, even if it couldn’t always entirely deliver, what we now know as a ‘safe space’ to simply enjoy the medium. Outside, in what might laughably be labelled ‘the real world’, comics readers older than the age of junior school pupils could be regarded with contempt, suspicion and even outright violence. (The Almanac will return to the latter in a coming entry.) But inside a Comicon, comics and merchandise could be freely bought without thinking about the disdain it might provoke among the general public. And, of course, given how hard it could be to even find recent titles in British newsagents, a convention stood as a thrilling, enticing and wallet-emptying arena for filling out a collection.

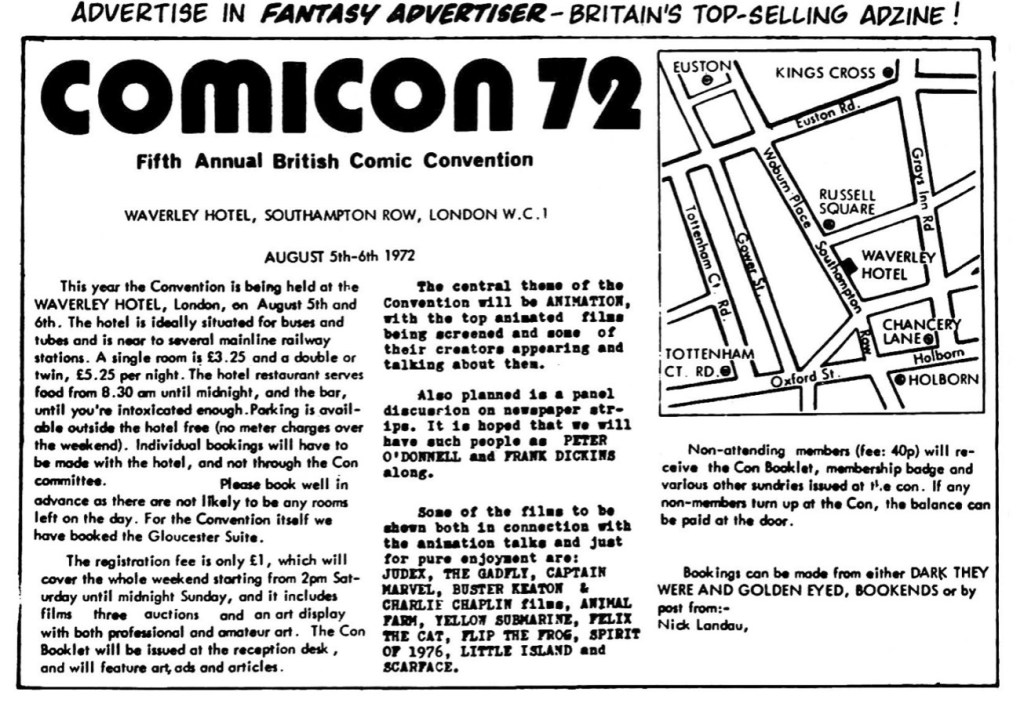

Amended and updated for publication in the same month’s Fantasy Advertiser #44, the Comicon ad now declared that the gathering’s theme would be animation and potential guests included Modesty Blaise’s co-creator Peter O’Donnell and newspaper strip cartoonist Frank Dickens. (Britain had at yet few professionals working in American comics and there appears to have been, understandably, no funds to wing either homegrown or indigenous talent working in the US across the ocean to the show.) In a time in which most fantastical screen productions, movie or TV, could be incredibly tough to see, the film and shows scheduled for the weekend would have also been a terrific draw.

To my own amazement, I note in these pieces that the groundbreaking London sci-fi/comic shop Dark They Were And Golden Eyed was already in situ in London’s Wardour Street. It was the first comics shop I ever heard of and the first I ever visited. I’d always believed it had opened in 1974, which was the year in which I’d first visited that long-lost, over-crowded, smoke-filled and entirely wonderful nexus of the fantastical. Now I find the thought of visiting the shop in 1972 and buying a ticket for a coming Comicon utterly beguiling.

The saga of 1972’s Comicon will continue at a later date in The Almanac Of The Fantastical.