Of course, the comics released into the American marketplace during this week wouldn’t be seen soon, if they were ever seen at all, in British newsagents. Not that most American fans had it, by all accounts, easy. Even there, in the promised land, as it seemed, comics never arrived in local shops, or, perhaps worst of all, were acquired, legally or sometimes not, by fellow comics devotees. But for those of us on the other side of The Big Pond, we had to wait months, and the selection that eventually arrived was likely to be severely limited.

But presuming you were around in the USA during 1972, and assuming that you had a full range of the titles recently pushed out into the world, these would be – in no particular order – my recommendations for the best of the bunch:

With Stan Lee having largely laid down his Marvel Comics responsibilities for plots, scripts and edits, Spider-Man had passed into the writerly hands of the young Gerry Conway. With the remarkable storytelling of longtime Spider-Man artist John Romita to collaborate with, Conway’s ideas felt both fresh and exciting. Perhaps influenced by the cultural prominence given to The Godfather, both novel and film, Spider-Man was dropped into a world in which super-villains and super-gangsters warred with each other. It was as if the legacy of 1930’s Dick Tracy had been embraced, spruced up and run with. Whether one result of this was an even greater degree of excitement and involvement on Romita’s part, the period saw his work at its most inventive and expressive. Conway even followed through on a way to shake up Peter Parker’s status quo without shattering it, namely, the presence of a duodenal ulcer.

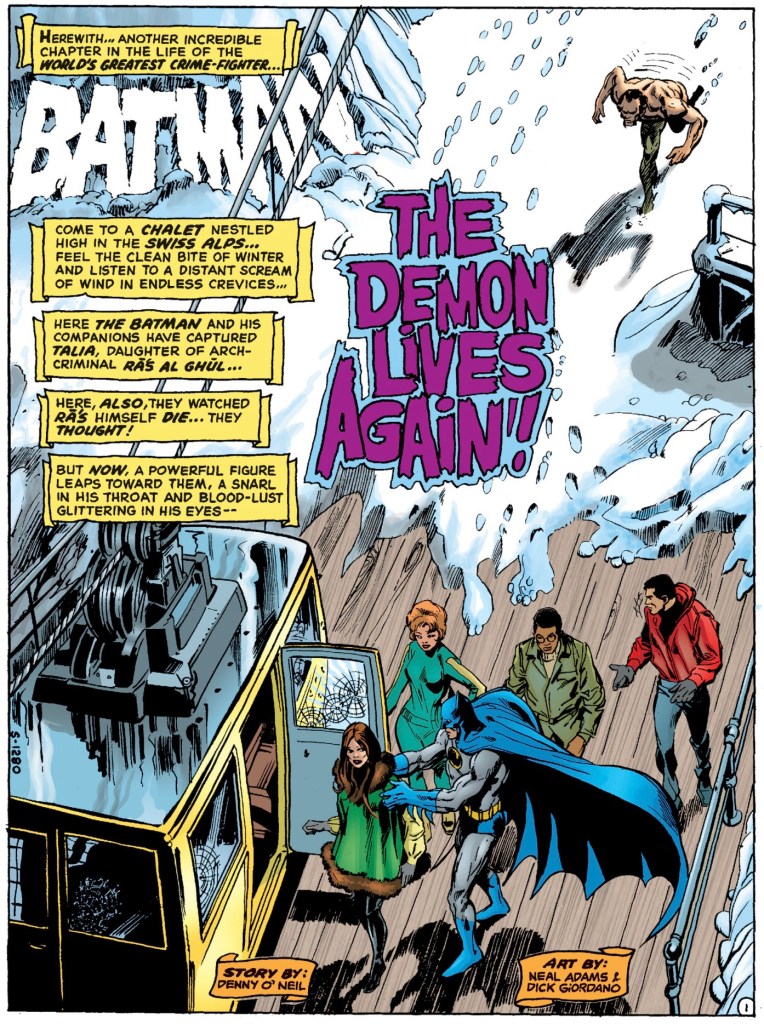

If the previous issue of Batman had felt like an awkward and only intermittently enjoyable mix of the innovative and the hackneyed, The Demon Lives Again works brilliantly well from beginning to end. In the invention of R’as al Ghul, who in this issue seems to grow from interesting protagonist to iconic arch-villain, O’Neil and Adams succeeded where so many have stumbled, namely, in the invention of an opposite number who bears comparison with the very best of Batman’s rogues gallery. The air of a big-budget screen thriller continues with a shift of locale from snow-capped mountains to a “fierce and merciless” desert, but unlike before, these cinematic backdrops feel key to the set-pieces that play out against them. The supporting cast, which had previously seemed irrelevant and unlikely, each have their moment too. All in all, the issue is every bit as much a triumph as its reputation would insist.

In the end, we’re left with two major developments in Batman’s set-up. He’s now a man who is willing to kill if he judges there’s no alternative, and he’s a passionate kisser too. The collaboration between O’Neil and Adams was soon to end, but it was a substantial and influential legacy that they’d leave behind, and this was an absolutely key part of it.

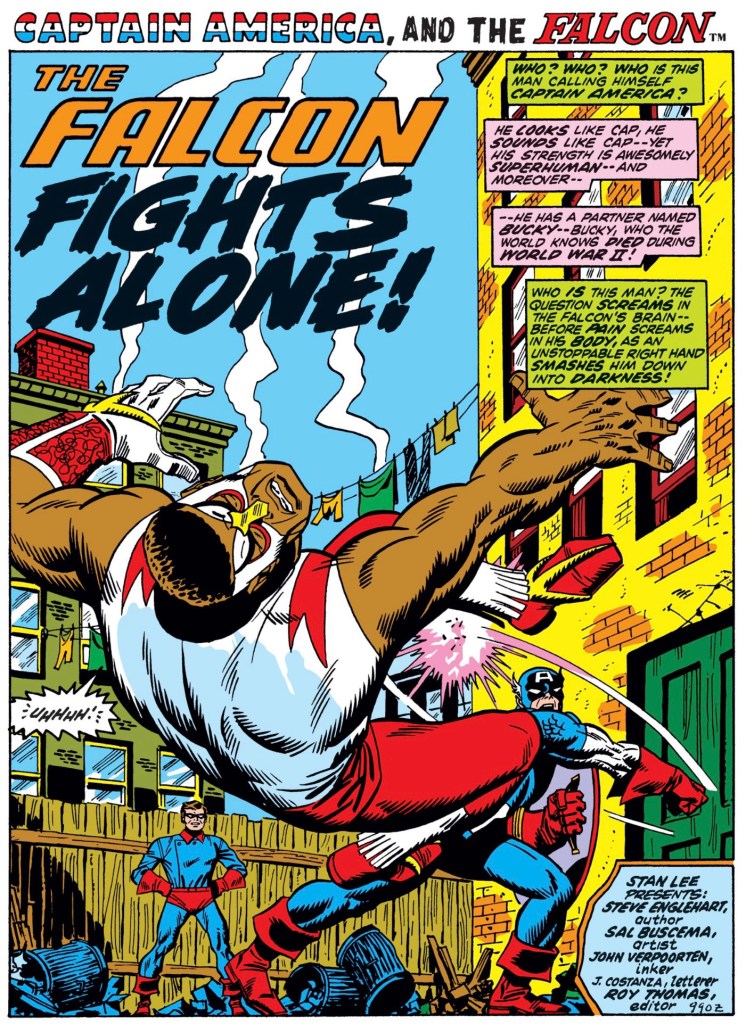

For the first time on his new stint on Captain America and The Falcon, Steve Englehart co-produced an issue that promised great things for the future. What had been perfectly adequate with speckles of promise became something far more substantial. With his collaborator Sal Buscema, whose presence Englehart loved for the artist’s crystal clear storytelling and fidelity to his plot’s details, the comic began to move on from tying up old plot-threads. (Those that lingered on were lent a deliberate purpose rather than being dismissed or ignored, which is always the sign of a careful and respectful franchise writer.) The promise of the previous issue’s conclusion, in which bizarre, red-baiting and self-evidently racist versions of Captain America and Bucky attacked The Falcon, was borne out in what was revealed to be the tale of the anti-Communist Cap who’d briefly appeared in a handful of 1950’s adventures. The playing out of continuity contradictions rarely make for interesting, let alone enthralling, reading. Yet Englehart and Buscema’s story used the corruption evident in Steve Roger’s McCarthy-era counterparts to open up a debate about what 1972’s Captain America actually stood for. It would a long-running theme in their stories which would take Rogers to the White House and a President who was as appalling as any super-villain faced in Cap’s own tales since the Red Skull.