On this day in 1972, heavy-blues trio The Groundhogs continued their only American tour with a concert at the Pocono International Raceway in Blakeslee, Pennsylvania. Their sole excursion across The Pond was soon to be curtailed by band leader Tony McPhee’s fall from a horse. By the 21st of this month, they’d be back in Blighty and recording a BBC session for performer and presenter Mike Harding.

In Blakesee, The Groundhogs’ set included two songs from their Who Will Save The World?: The Mighty Groundhogs LP, which had been released on March 3rd: Music Is The Food Of Love and their cover version of Amazing Grace. For our purposes, the album’s cover design was as fantastical as any other released in 1972, portraying as it did McPhee, Peter Cruikshank and Ken Pustelnik as superheroes.

Authenticity was a quality much valued by the underground bands of the period. And just as The Groundhogs had always stayed true to their own conception of how a people’s blues rock band should sound and look and behave, the choice of cover artist for the album reflected a love for the superhero comic combined with a knowledge of its current heights. For the American storyteller Neal Adams had been commissioned to both create the cover and illustrate the strip which played out across the album’s fold-out packaging. Where some other European acts had doffed their caps towards Marvel and DC, sincerely or less so, using artists from outside the costumed crimefighting tradition, The Groundhogs were depicted by the age’s premiere superhero artist. Playful the cover undeniably was, but authenticity and playfulness needn’t be considered opposites. The artwork by Adams was unmistakably The Real Deal, as dynamically contemporary as anything by even the best of his super-box contemporaries. In referring to Adams in the LP’s credits box as “The Nefarious”, the cover even captured Stan Lee’s habit of lending his collaborators snappy, absurd nicknames. The implications were clear: the American superhero was loved and respected by at least one person in The Groundhog’s inner circle, even as America the super-capitalist superpower often behaved as a super-villainous cabal.

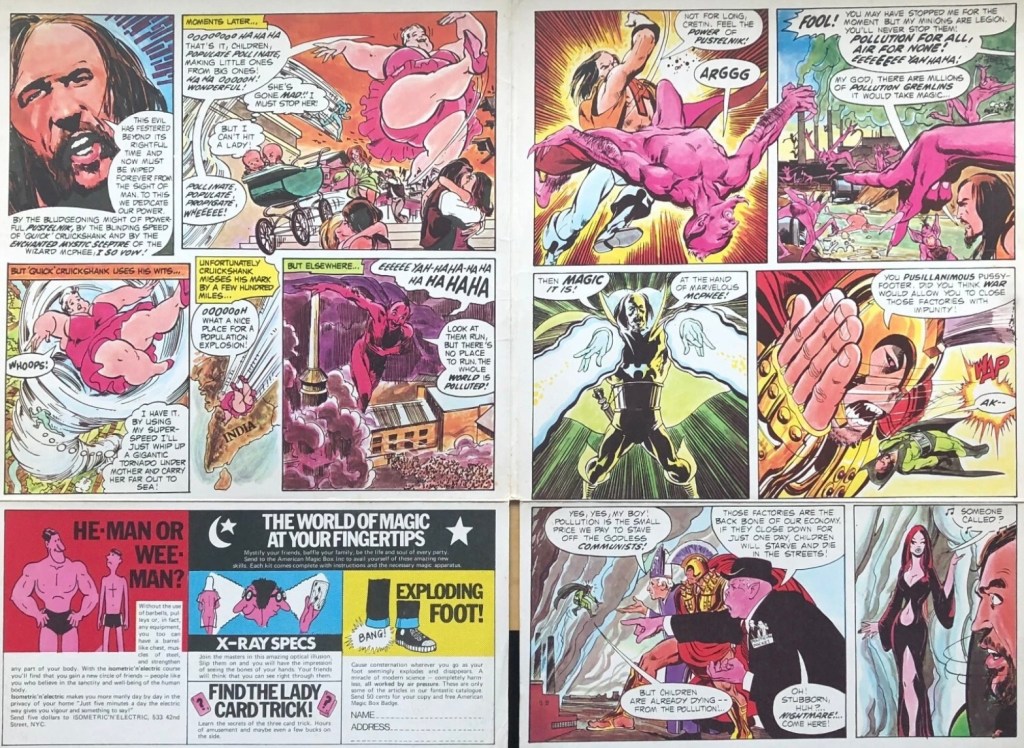

Reflecting the lyrical concerns of the album’s songs, Adams’ art pitted the (super) Groundhogs against representations of Malthusian doom, environmental despoliation, the reactionary ideologies of religion and politics, and the underworld selling addictive drugs to the vulnerable.

Alongside all of that, Adams’ artwork featured several faux adverts, parodying their cheap, cheerful and shamelessly exploitative fellows in the US comicbook throughout the decades.

Just as authenticity doesn’t preclude good humour, it’s also a quality that can prosper even in the midst of experimentation. The Mighty Groundhogs saw McPhee leading his colleagues in the much greater use of keyboards and a mellotron. The result was an album which presented, in Andrew Male’s words for Mojo Magazine, “a dark, disorientating sci-fi journey through a cyanide-poisoned Earth that’s “just a cage seven thousand miles wide!”. Even in the midst of Julian Cope’s hugely enthusiastic 2003 review of the record stands the recognition that it can often seem as if “the entire album is set in a world of eternal overcast”. As such, there wasn’t much to smile along with in the album’s tracks for anyone tuning into its lyrics. But Adams’ artwork helped to lend a welcoming and good humoured context to all this very early-70s mix of righteous finger-pointing and apocalyptical future-casting. It was a cover that worked every bit as much as a counterweight as it did as a harbinger of an album dedicated to, in the language of the time, heavy thinking.

Fun in itself, and a truly impressive example of a band using an album’s packaging to create a much broader context in which to frame their music, the comic strip offered colour and action and humour to an LP that often lacked those qualities. The strip even allowed the myth of the superhero to be punctured. In showing that even The Mighty Groundhogs themselves can’t defeat with magic blasts and fisticuffs the super-villains who stand against them, the pernicious legend of vigilante justice is, with a smile and a wink, laid in the ground. Even as it sounds a touch vainglorious to conclude on the note that The Groundhogs as a band might, through communication with their audience, achieve far more than they ever could as superheroes, it’s an entirely valid point. The wider events of the time seemed to insist exactly that. The violence practised by urban guerrillas from The Weathermen through to The Angry Brigade and on to The Baader-Meinhof gang, had achieved nothing but death and destruction and the intensification of state oppression. Wherever The Revolution was going to come from, and if it was going to arrive at all, it would require a quite different set of solutions to code-names, secret identities and hyper-violence. Even the noble and well-intentioned Mighty Groundhogs, it seemed, with their costumes and fists, were going to have to envisage a far longer and far harder road to a clean and peaceful globe than they’d hoped for. But then, it appears they knew that …